|

Prologue "Knowledge is power" (Sir Francis Bacon, Religious Meditations, Of Heresies, 1597). "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely" (Lord Acton, Letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton, 1887).

Another, sometimes more efficient way is structural: by carefully defining various constituencies, granting them measured powers, and prescribing procedures for the exercise of their powers, all in such a way as to create a structure in which each of the constituencies, by virtue of its own self-interest and nature, is inherently qualified and motivated to restrain the others in the exercise of their respective powers. This approach is called a separation of interests and powers; and it, together with regulation, constitute "checks and balances." James Madison studied other nations' systems of government before authoring the US Constitution; that's why he engineered checks and balances into the US's DNA (and it held up pretty well, for pretty long . . . it's also why it can sometimes work to give people the ability to file class action suits, etc. . . . but those are other stories). So here are the Ten Things: In the US and elsewhere, we've developed a serious imbalance, in that governments and big businesses know everything about us, and we know less and less about them. The power of knowledge has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of relatively few, powerful elites.

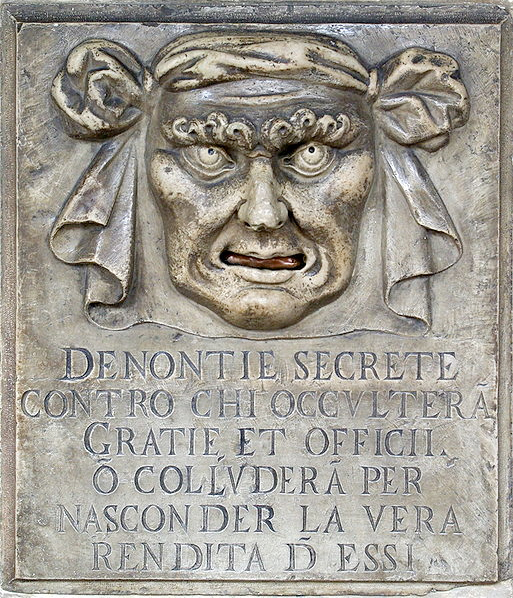

But there's a lot – including some of the things we care about most intensely – that isn't shared on the telephone or in e-mails; things that are said only in bed, or to a relative, or to a friend during a walk in a forest. How do governments get that information? They use the power of the knowledge they've already acquired through wiretaps, data mining, etc. to blackmail people into revealing it. As Ellsberg put it, you want your daughter to go to college, you want this or don't want that; they find out what you want and what you fear, in order to make us into a nation of informants, which is what the G.D.R. was. I'd add that, through the cloud-based surveys and questionnaires we fill out and games we play on Facebook and elsewhere, the government and others also have access to a great deal of info that can be used not just as leverage but also to manipulate us psychologically and without our even being aware of it. At the same time, as Ellsberg pointed out, the government wants opacity as to its own operations; it wants us to know only what it wants us to know. And as the US government has classified more and more information, and as ownership of the media in the US and worldwide – the media that should ideally have been functioning as the "watchdog of democracy," monitoring those in power and exposing any abuse – has become more and more consolidated in the hands of a few megacorporations, government has in fact become less accountable, and more and more opaque. Wikileaks fired the first shots seriously puncturing that opacity in quite a while, thus triggering what John Perry Barlow called "[t]he first serious infowar." (For more about the case for Wikileaks and similar facilities, see "The Case for Wikileaks.") [Note: People sometimes speak as if there's an insoluble dilemma between transparency and privacy; this is false. Simply put, the more power one has over others, the more transparency one owes them; those with the least power should enjoy the greatest privacy.] [P.S.: TPTB are more aware than we of our power; but our power extends no farther than our awareness.] The potential to help restore the balance of knowledge and thus the balance of power between the oligarchs and the rest of us constitutes what I've regarded as the most important effect of Wikileaks' revelations. As with respect to many brilliant innovations, the basic concept of Wikileaks may seem obvious now, but I'm aware of nothing quite like it before.

Assange has pointed out three benefits to Wikileaks' strategy of publishing the secrets of the powerful. The first benefit consists in that it's only when we know about an injustice that we can do something about it. He states a second benefit in the SVT documentary, WikiRebels: that "[e]very release that [Wikileaks publishes] has a second message: if you engage in immoral, in unjust behavior, it will be found out." I.e., exposure of past bad acts tends to deter future bad acts. (At least, that is, if such exposure results in bad consequences to the bad actors – a noteworthy qualification.) The third benefit is revealed in Assange's writings, among the most fascinating I've read on the strategic aspects of the current infowar; in particular, see "State and Terrorist Conspiracies" and "Conspiracy as Governance" (2006) and also Assange's post on his site, IQ.org, "Sun 31 Dec 2006 : The non linear effects of leaks on unjust systems of governance" (unfortunately, as of this writing, the site appears to have been taken down). Assange begins by observing that corrupt governments (or, I expect, other organizations) are inevitably conspiratorial because their efforts to exploit people and interfere with their liberties tend to inspire resistance. So, in order for such regimes to maintain their authority, they must try to keep the nature of what they're doing secret, restricting certain information to those who are inside the regime or otherwise in on the exploitation or otherwise beholden to them. (If they were maintaining their power legitimately, there'd be no need for secrecy; the more secrets there are, it would seem, the more likely that the regimes keeping them are corrupt.) Assange further describes organizations such as governments as computational systems and proposes that, when their secrecy is threatened, they tend to try to tighten their security, throttling down the flow of information internally as well as externally. In that event, as a result of this throttling down, the system becomes "dumber," since those within it become less able or willing to share all the info and ideas needed in order for the regime to act as effectively in its own behalf as it otherwise could (i.e., as Assange notes, "garbage in, garbage out"). This has of course been exactly the US State Department's complaint: that governments that aren't telling their own citizens what they're really up to will also stop telling our government – will, in fact, stop conspiring with our government, at least insofar as secret-sharing constitutes conspiracy. (Note that this amounts to an admission that our government is engaging in a "conspiracy," as defined by Assange, with other governments – that all the governments involved are conspiring with one another at least in keeping secrets from their own peoples. This raises the possibility that authorities' real concern with respect to the publication of the US cables is not in fact re- US interests as against other countries', but rather re- the interests of the ruling class to the extent those are against the interests of those ruled. Basically, the oligarchs of the planet – those who have accumulated enough wealth and/or weapons and/or p.r. facilities (see Thing No. 4 below) to subdue their local populations – are like kids cheating at Monopoly: I'll help you get the better of your peons if you'll help me get the better of mine.) These writings suggest that part of Assange's strategy of publishing the secrets of a corrupt regime may actually be to provoke the regime to tighten its security, thereby bringing about a degradation of its organizational I.Q. that should render the regime more vulnerable and ultimately hasten its downfall or reform. (Oh, what a tangled web we weave!) (UPDATE: I just came across an excellent piece by Aaron Bady quoting relevant portions of Assange's writings and unpacking this point in detail, at zunguzungu.) If this is in fact part of the Exposure Strategy as practiced by Wikileaks, the "throttling down" seems to be proceeding like clockwork. Interestingly, Fox News has reported that "Davos expert says hiding less information is best."

(There is, of course, at least a fourth prong, so to speak, to Assange's strategy: his insurance file.) In numbers and resources, Assange and Wikileaks are "Davids" in comparison to the "Goliaths" they're up against. Inasmuch as knowledge is power, however, the might of truth on their side gives them the potential to trigger gigantic change. Truth isn't the only weapon in the infowar, and that brings us to an important part of the strategic picture that Assange does not much discuss: p.r. I believe he does not discuss it, not because he fails to appreciate its importance but because, at least so far, it has not been to his advantage to do so. For p.r. can overcome much if not most of the strategic benefits of the Exposure Strategy. Sigmund Freud's nephew, Edward Bernays, invented the science of "public relations," together with the name that exemplifies it, in the 1920's based on his uncle's theories. Adam Curtis's documentary for the BBC, Century of the Self (all four parts of which can be seen here or at the Internet Archive) does a terrific job of setting out the history of p.r. and its impact on our society, and I recommend it highly; see also Wikipedia on Edward Bernays. His writings, including Propaganda (1928) and Manipulating Public Opinion (1928), make plain that the science goes far beyond mere touting or other more ordinary kinds of persuasion. The new, psychoanalytically-derived techniques were innovative in at least two important respects. First, they are deliberately designed to stimulate and appeal to our most basic, powerful urges – fear, anger, greed, and lust. Second, they are designed to influence us without our awareness, with the real message camouflaged as incidental to some other purpose, or coming from a source disguised as a disinterested, objective authority. For example, Bernays invented the use of front organizations designed to appear disinterested but that really exist only to promote a product or idea for the benefit of a hidden commercial or political constituency. He also invented the focus group, in which those conducting the group pretend interest in our considered opinions but are really looking for clues we inadvertently reveal about our unconscious emotions and desires, feelings we might not admit to or even recognize if asked but which, with or without our awareness, often drive our behavior.

In Propaganda, Bernays wrote, "Those who manipulate [the] unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. . . . We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of." He knew, because they accomplished it with his well-rewarded help. The p.r. industry has grown exponentially since Bernays time (see, e.g., "PR Industry Fills Vacuum Left by Shrinking Newsrooms": "there were more PR people representing those companies [at hearings on BP's Gulf oil spill] than there were reporters in attendance"), because it works. Maybe not on all the people, all of the time, but enough so that the investment pays off. (Curtis argues further that, after decades of immersion in the p.r. resulting from these techniques, we've gone from being first and foremost citizens who recognize that it's sometimes in our best interests to unite in collective action to make the world better for others as well as ourselves, to – rightly or benightedly – relatively passive, atomized consumers focussed on the marketplace as a main source for our individual identity support and fulfillment and who who secretly feel entitled to prioritize gratification of our every self-centered whim. We feel we are free, but in reality, we've been enslaved through our unconscious instincts and emotions.) When this kind of p.r. is deployed successfully, the facts simply no longer matter; it's as if we've been immunized against truth. Thus, e.g., revelations in recent years of war crimes and gross violations of Constitutional law by US officials, and even of US propaganda illegally directed at its own citizens (see here and here), as well as many other gross violations of our fundamental rights and known crimes by the powerful, have elicited little outcry. In short, p.r. is info's kryptonite. (On somewhat related subject, there's the "Nobody Heard What You Said" story, recorded by Jay Rosen at PRESSthink:

I'd also like to recommend the New Yorker article, "Twilight of the Books," on the effects of the rise in TV watching and relative decline in reading. Among other things, it describes studies suggesting that proficient readers may think differently than people who rely more on visual communication. While both kinds of thinking are probably valuable, it appears that, generally, visual communication involves thinking oriented toward graphic, functional-narrative or emotional content, while reading facilitates abstract reasoning and an ability to compare and contrast subject-matter based on a wider array of kinds of logic. Also, studies have shown that TV has much in common with both addiction and brainwashing – see here, here, and here. TV is unusual in that on the one hand, the brains of people watching it appear much more inert than usual, with their critical faculties turned almost completely off, while on the other hand, they are nonetheless absorbing the commercial and other messages being transmitted. In a similar vein, see the infamous “Nobody heard what you said” story here.) Note that, to the extent "public relations" is effective, it neutralizes all three prongs of the Exposure Strategy; i.e.,

As I've also suggested, Assange's insight into the cost of tightened secrecy to organizational I.Q. sheds new light on why Edward Bernays' invention was such a boon to the the powerful – because "public relations" enables them to manipulate populations through their basic instincts and emotions, rather than through secrecy. To the extent p.r. is successful, it helps corrupt regimes maintain control without having to compromise their own systems' computational power. It would seem that the combination of a moderate level of secrecy with a lot of p.r. might enable a regime to maintain itself longer while still engaging in a higher level of corruption than possible if the regime relied on either secrecy or p.r. alone, and also without relying too heavily on brute force. (Not to mention the fact that since the powers that be now know so much about us, they're well-prepared to take out any troublemakers.) The US government's efforts to manipulate public opinion about Wikileaks started long ago (see, e.g., Salon) and has been highly effective. Within a p.r. environment as powerful and immersive as ours, efforts such as Wikileaks' to publish truth might well be rendered moot. So this is an infowar and a p.r. war. The traditional media still reach many more people than do non-traditional media and can nullify the impact of the truth by simply ignoring it – or if that doesn't work, by discounting or even directly contradicting it – and if that's not sufficient, by smearing and attacking its sources – and if that doesn't do it, by inciting our fear and anger to blind us.

The onslaught of p.r. aimed at neutralizing Wikileaks and Assange has been extraordinary, even in our p.r.-saturated times. An appreciation of the power of p.r. and the extent to which Americans and others are already influenced if not controlled by it may be partly why Assange may have believed it necessary for an infowar to happen more or less now. Because the powerful do not yet fully control the non-traditional media, but they're making excellent progress on it. And once the powerful have acquired effective control of non-traditional media too, it's not just that they'll be better able to keep their secrets; it's also that there will be no escape from their p.r./propaganda; we'll be fully immersed, à la Altered States. For Assange, a key consideration may have been when to trigger the infowar: it would be best for it to occur when the internet has grown to reach the greatest possible number of people but before it's been converted into the most powerful instrument of mass surveillance and mind control ever created. (UPDATE: Cf. Assange in this interview published May 2, 2011: "Facebook in particular is the most appalling spying machine that has ever been invented. . . . " {see also here.}) I gather it may have been disagreement regarding the timing and manner of publication of the leaked US cables that gave rise to the split between Assange and those defecting to form OpenLeaks – that Assange wanted to publish the info sooner and in a more provocative manner. Indeed, one might wonder whether the "split" is real – whether the Wikileaks people may have decided the best strategy would be for the colorful Assange to use WL to draw off the oligarchs' fire and maximize attention to the story, while OpenLeaks continues WL's original, less sensational operations. In a fine irony, the WL people would be deploying one of the oligarchs' own favorite tactics against them: when one organization gets in trouble, senior managers just form a new one and carry on business as usual (similarly, Assange has stated that Wikileaks has "us[ed] every trick in the book that multinational companies use to route money through tax havens – instead we route information"; see his speech at the Oslo Freedom Forum 2010). Unfortunately, I fear this conjecture is probably overly optimistic. But Okke Ornstein has noted other evidence of Assange's "grand strategic thinking." [UPDATE: The split consisted in the defection of Daniel Domscheit-Berg, who took with him leaked information regarding Bank of America et al. OpenLeaks never in fact became operational. “WikiLeaks and other sources later confirmed the destruction of over 3500 unpublished whistleblower communications, with some communications containing hundreds of documents, including the US government's No Fly List, 5 GB of Bank of America leaks, insider information from 20 right-wing organizations and proof of torture and government abuse of a Latin American country.” (Quote retrieved 2015-11-05 from Wikipedia.)] It's also interesting to speculate about exactly what it is that prompted the powerful to bring out the big guns. Was it the content of the US State Dept. cables? Was it that material leaked from within a major US bank is expected to be published next? Or was it the fact that the info is now being reported not just by a lone, rebel website but by the great newspapers of the world? For it was when Wikileaked stories covered half the front page of The New York Times that citizens began to sit up and pay attention. (Or was it that they, too, recognized that we're at a crucial juncture, a time when a critical mass of the people might actually still sit up and take the red pill?) But The NYT itself isn't exactly independent from the powers that be. What if sufficient numbers of people won't listen to the truth unless it comes through outlets like The NYT? What if The NYT et al. refuse to continue to publish it (as The NYT has done so often before)? Are we about to find out that we are, in fact, living in a post-reality world? I've had a few quotations in my head lately:

(The emphasis in the foregoing and other quotations in this essay is supplied.) Go to P. 2

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||